We are learning more about how airborne dust affects the climate thanks to NASA’s Earth Surface Mineral Dust Source Investigation (EMIT) project, which is measuring the presence of important minerals in the planet’s dust-producing deserts. However, EMIT has also proven it is capable of detecting methane, a powerful greenhouse gas.

What Are These “Super-Emitters”?

The science team has discovered more than 50 “super-emitters” across Central Asia, the Middle East, and the Southwestern United States in the data EMIT has gathered since it was deployed on the International Space Station in July.

Super-emitters are buildings, pieces of machinery, and other infrastructure that emit methane at high rates, usually in the fossil fuel, waste management, or agricultural industries.

Related: How does climate change impact our health?

The Impact Of Methane In Pollution

Methane emissions must be controlled if global warming is to be prevented. According to NASA Administrator Bill Nelson, this innovative new breakthrough will not only help researchers better understand where methane leaks are occurring but also offer guidance on how to promptly address them.

“For years, NASA’s more than two dozen satellites and in-space instruments, including the International Space Station, have been crucial in identifying changes to the Earth’s climate. In order to quantify this powerful greenhouse gas and halt it at the source, EMIT is proving to be an essential tool in our toolkit.”

Methane absorbs infrared light in a distinctive pattern known as a spectral fingerprint, which EMIT’s imaging spectrometer can identify with great accuracy and precision. Carbon dioxide can also be measured using the device.

Significance Of EMIT

The new observations result from EMIT’s ability to scan expanses of the Earth’s surface dozens of miles wide while resolving areas as tiny as a soccer field, as well as from the wide coverage of the globe provided by the space station’s orbit.

According to David Thompson, senior research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, which oversees the mission,

“These results are exceptional and they demonstrate the value of pairing global-scale perspective with the resolution required to identify methane point sources, down to the facility scale.”

Thompson is also the instrument scientist for the EMIT satellite. Its special capabilities will increase the bar for efforts to identify methane sources and reduce emissions caused by human activity.

Why Is Methane More Harmful Than Carbon dioxide?

Methane contributes only a small portion of greenhouse gas emissions created by humans compared to carbon dioxide, but it is thought to be 80 times more efficient, tonne for tonne, at trapping heat in the atmosphere in the 20 years following release.

Furthermore, whereas methane persists for only about ten years, carbon dioxide does so for hundreds of years. As a result, if emissions are decreased, the atmosphere will react in a similar amount of time, resulting in a slower near-term warming.

How Can We Reduce Methane?

A crucial part of the procedure can be locating methane point sources. Operators of the buildings, machinery, and infrastructure that generate the gas can swiftly take action to reduce emissions if they are aware of the locations of major emitters.

Scientists checked the accuracy of the imaging spectrometer’s mineral data as they made methane observations with EMIT. EMIT will measure the surface minerals in dry regions of Africa, Asia, North and South America, and Australia for the course of its mission.

Researchers will be able to better comprehend the effects of airborne dust particles on the surface and atmosphere of Earth as a result of the data.

Kate Calvin, NASA’s principal scientist and senior climate advisor, said, “We have been anxious to see how EMIT’s mineral data could improve climate modeling.” “This new methane-detecting capability presents a unique opportunity to quantify and monitor greenhouse gasses that contribute to climate change,” the study authors write.

Methane Plume Detection

In order to evaluate the imaging spectrometer’s capabilities, researchers can search for methane in the mission’s study area, which overlaps with known methane hotspots throughout the globe.

The EMIT methane effort is being led by research technologist Andrew Thorpe at JPL. “Some of the plumes EMIT detected are among the largest ever seen – unlike anything that has ever been observed from space,” he said. What we’ve discovered in a short period of time has already surpassed our expectations.

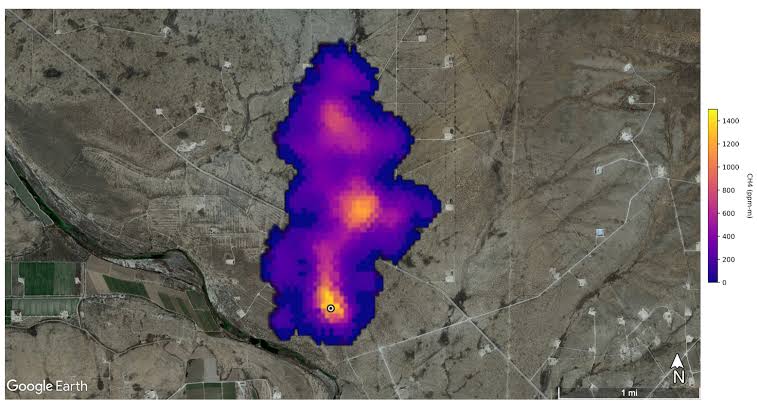

For instance, the sensor located a plume in the Permian Basin, southeast of Carlsbad, New Mexico, that was roughly 2 miles (3.3 kilometers) long. The Permian, one of the world’s biggest oil fields, extends across portions of southern New Mexico and western Texas.

East of the Caspian Sea port city of Hazar, EMIT researchers in Turkmenistan found 12 plumes from oil and gas infrastructure. Some plumes that are blowing to the west are more than 20 miles long (32 kilometers).

Is There Any Other Methane Plume?

The scientists also located a methane plume from a sizable waste-processing complex that was at least 3 miles (4.8 kilometers) long and located south of Tehran, Iran. Decomposition produces methane, and landfills can be a significant source of this gas.

The Permian site is expected to flow at a rate of around 40,300 pounds (18,300 kilogrammes) per hour, the Turkmenistan sources combined at 111,000 pounds (50,400 kilogrammes) per hour, and the Iranian site at 18,700 pounds (8,500 kilogrammes) per hour, according to scientists.

The combined flow rate of the Turkmenistan sources is comparable to that of the Aliso Canyon gas leak in 2015, which occasionally topped 110,000 pounds (50,000 kg) per hour. One of the greatest methane emissions in American history occurred in the Los Angeles region.

Conclusion

EMIT has the potential to discover hundreds of super-emitters, some of which have already been identified through air, space, or ground-based measurement, and others which were previously unknown.

EMIT’s lead investigator at JPL, Robert Green, predicted that as it continues to study the earth, it “will notice regions in which no one thought to search for greenhouse-gas emitters previously, and it will find plumes that no one expects.”

In a new class of spaceborne imaging spectrometers, EMIT is the first one to examine Earth. One illustration is the Carbon Plume Mapper (CPM), a device being developed at JPL that can detect carbon dioxide and methane. To launch two satellites with CPM in late 2023, JPL is collaborating with other companies and a nonprofit organization called Carbon Mapper.