A mild G1 geomagnetic storm will be caused by solar winds that will hit the Earth today (20 July) or tomorrow (21 July) as a result of the Sun’s massive “canyon of fire” filament splitting.

According to some sources, solar filaments were initially observed on July 12 as dark, thread-like threads against the Sun’s dazzling background.

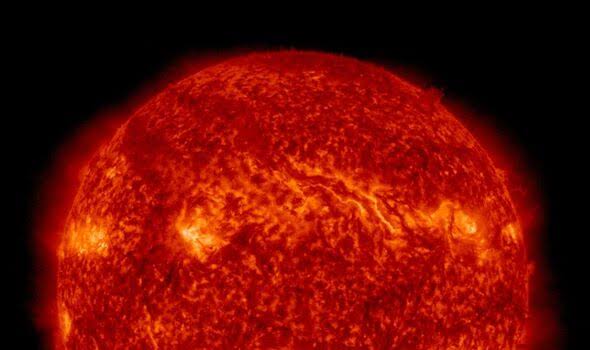

Then, on July 15, a filament that had been snaking its way down the northern hemisphere of our star burst, carving out a roughly 238,880-mile-long (384,400-kilometer) and 12,400-mile-deep (20,000-kilometer) “canyon of fire” on the surface of the Sun and spouting solar material directly at us.

What Happens In A Solar Flare?

Huge arcs of electrified gas (or plasma) known as solar filaments snake through the Sun’s atmosphere at the whims of the star’s tremendous magnetic field.

These enormous magnetic tubes can support enormous amounts of plasma above the Sun’s surface, but they are also extremely unstable, and when they crash, they can send coronal mass ejections (CMEs), which are powerful jets of solar wind, hurtling toward Earth.

A space weather physicist named Tamitha Skov described the eruption’s aftermath on Twitter as “a magnificent ballet” as the long, snake-like filament cartwheeled its way off the Sun.

“It will be difficult to forecast the magnetic orientation of this Earth-directed solar storm. If this storm’s magnetic field is facing south, G2-level (possibly G3) conditions could develop!”

What Are These G2 And G3 Storms?

Storms classified as G2 and G3 are thought to be moderate and strong, respectively.

The CME that was released when the filament collapsed is expected to strike Earth today or tomorrow. Strong magnetic fields, like the one on our planet, absorb the bombardment of solar debris from CMEs and cause violent geomagnetic storms.

These storms cause waves of extremely energetic particles to slightly compress Earth’s magnetic field. These waves then trickle down magnetic-field lines near the poles, where they agitate atmospheric molecules and release energy in the form of light to produce auroras that are colorful and resemble the Northern Lights.

Is This Storm Concerning?

Fortunately, the storm emanating from this filament is not very strong. It is categorized as a G1 solar storm and could, albeit not significantly, affect various satellite operations, notably those for GPS and mobile devices, and power grid irregularities. Additionally, it will bring the aurora as far south as Maine and Michigan.

These geomagnetic storms can disrupt our planet’s magnetic field so severely that they can send satellites hurtling toward Earth. Additionally, scientists have warned that extreme geomagnetic storms could even bring down the internet.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Space Weather Prediction Center estimates that erupting debris from CMEs typically travels to Earth in between 15 and 18 hours, although it can move more slowly and take longer, as was the case with this CME.

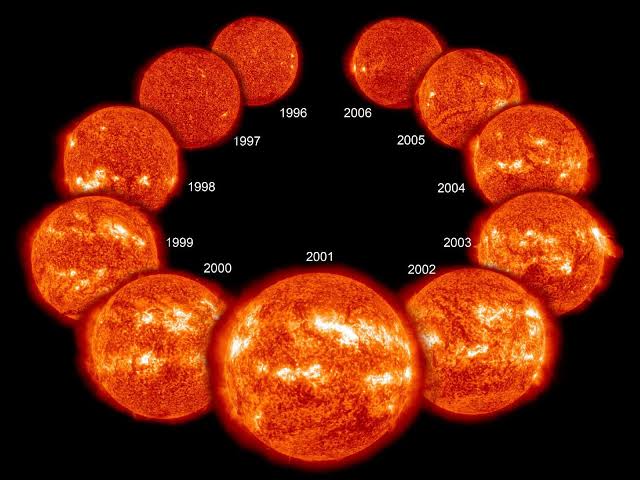

The Series Solar Cycles

The Sun is at the most active part of its roughly 11-year solar cycle as this storm develops. It is Earth’s second solar storm in the last twenty-four hours.

Solar activity cycles up and down, as has been known to astronomers since 1775, but recently the Sun has been more active than anticipated, with roughly twice as many sunspot sightings as NOAA had forecast.

The Sun’s activity is anticipated to increase steadily over the coming years, peaking in 2025, before declining once more.

A new model for the Sun’s activity was put forth in a paper that was published on July 20 in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics. The method, according to the paper’s authors, could be used to improve solar forecasts, involving separately counting sunspots in each hemisphere.

Conclusion.

According to scientists, the 1859 Carrington Event, which generated nearly the same energy as 10 billion 1-megaton atomic bombs, was the greatest solar storm ever seen in modern history.

The strong stream of solar particles that hit Earth wrecked telegraph lines all over the world and caused auroras to shine as far south as the Caribbean that were brighter than the full moon’s light.

Similar to the 1989 solar storm that generated a billion-ton plasma plume and triggered a blackout throughout the whole Canadian province of Quebec, scientists warn that a similar event today might result in trillions of dollars in damage and widespread blackouts.